Clash

Responding to an Argument

Your long-time romantic partner comes to you and says, “You don’t love me anymore.” You just stand there. Stunned. Too startled to speak. Hearing you not say anything your partner turns around walks away saying, “That’s what I thought.”

What just happened? Because you did not respond, your partner assumed you agreed with the statement. Your failure to engage in an argument implied that you had nothing to contradict the statement. Your failure to clash led to the belief that you agreed with the statement, thus no argument.

If you do disagree with someone’s statement, you need to learn how to clash with him or her.

If we look at this interaction through the lenses of this text, your partner is considered the pro-side, because they have made the claim that you don't love them. They have presented their argument which in this case is just the statement of the claim “You don't love me.” You, the con-side, must now respond or else the pro-side’s position is upheld automatically. Why? “Silence means consent.”

The famous maxim, “Silence means consent,” means that if the pro-side makes an argument and the con-side says nothing, the implication is that the con-side agrees with the pro-side. There is no controversy, thus no argument.

I was writing a letter that was going out to all the members of an organization to which I belong. I sent out a final draft to the nine committee members for one last check. I heard from three of them. I did not hear from the other six members, so I reasonably assumed that they had no objections.

Now I agree that in a social situation, silence could mean that the person is merely tired of arguing. They still may not agree, but they no longer want to spend the time or energy fighting. In a structured argument, however, it is important for those who disagree to fulfill their responsibility and respond to the initial argument. If not, the argument is over.

Clash occurs when there is a disagreement. In an argument, responding to the pro-side is referred to as "clash." When the pro-side presents their argument and the con-side says nothing, there is no clash. Only when the con-side makes their argument against the pro-side does clash occur, and then we have a genuine argument.

Skepticism

Our first step involves being skeptical of new ideas and arguments. When someone tells you something or you read it over the internet or see it on television, are you more likely to believe it or disbelieve it? As long as it does not clash with previous beliefs we hold, science suggests that we are more likely to accept new information. In fact, in order to understand a new concept our minds must first accept the concept to even understand what it means.

In a landmark 1991 paper, Harvard psychologist Dan Gilbert proposed that we process information in two steps. First, we accept information as true, and then we interrogate whether it may actually be false. In other words, we let the Trojan horse past the gate before we check to see if it’s full of Greek soldiers. “Humans,” wrote Gilbert, are “very credulous creatures who find it very easy to believe and very difficult to doubt.”

Cognitive Science Offers Tools To Rebuff Climate Deniers 1

- As Dan Gilbert argues, understanding a new idea requires two steps.

- Accept that the new information is accurate to understand the new ideas.

Once the ideas are understood, then test them to see if they are accurate.

-

Silence Does Not Always Mean Consent, Especially in Romance

-

Silence means consent is not an actual legal term and should not actually be relied on for all situations. This is especially accurate when “romance” is involved. More and more social situations, however, demand that if romantic advances are being made by an individual, that person must receive an affirmation of those advances before the romance is continued. Silence here does not mean consent.

But as you might imagine, once we accept the accuracy of a concept it becomes a challenge to then reject it. Since we are naturally prone to accept new information, our human nature is not to be initially skeptical. Being skeptical is a skill we must develop.

Our skepticism skill is challenged even more when we are presented with many “lies.” Again, Jeremy Deaton writes:

- Human brains are built to ward off singular untruths, but we struggle against an army.

When faced with an onslaught of lies, our defenses falter, letting alternative facts

slip past the barricade. There are several reasons why this is the case. Here are

three:It takes energy to scrutinize a lie.

- It takes more energy to scrutinize it when we hear that lie again and again.

- We don’t like to scrutinize a lie that supports our worldview.2

There is a misconception over what it means to be skeptical and I am guessing that now is a good time to clearly define what it means to be skeptical. Michael Shermer is the publisher of Skeptic magazine and is frequently asked what it means to be a skeptic. He answers this question by saying,

As the publisher of Skeptic magazine, I am often asked what I mean by skepticism, and if I’m skeptical of everything or if I actually believe anything. Skepticism is not a position that you stake out ahead of time and stick to no matter what.

...science and skepticism are synonymous, and in both cases, it’s okay to change your mind if the evidence changes. It all comes down to this question: What are the facts in support or against a particular claim?

There is also a popular notion that skeptics are closed-minded. Some even call us cynics. In principle, skeptics are neither closed-minded nor cynical. We are curious but cautious.3

This passage by Shermer points out four key thoughts about skeptics:

- No position is staked out ahead of time. This allows for you to examine the argument with an open mind and then decide whether you accept it or reject it.

- Skepticism follows the procedure of scientific inquiry looking to see if the evidence provided in the argument adequately supports the claim.

- It is okay to change your mind. You may have one position, but after listening to a new argument, with new and additional evidence you can now make a better decision and actually changing your mind is a good thing.

- Skeptics are not cynics. Instead Skeptics are curious, but are cautious and resist leaping to a comfortable conclusion.

An additional and often used method of learning a concept is to look at the origin of a word. For those of you who want to impress your friends, the term for this is etymology. The Basics of Philosophy website has a nice, brief examination of the term skeptic.

The term is derived from the Greek verb "skeptomai" (which means "to look carefully, to reflect"), and the early Greek Skeptics were known as the Skeptikoi. In everyday usage, Skepticism refers to an attitude of doubt or incredulity, either in general or toward a particular object, or to any doubting or questioning attitude or state of mind. It is effectively the opposite of dogmatism, the idea that established beliefs are not to be disputed,doubted or diverged from.4 (Maston,2008)

I like the idea that this passage clearly states that being a skeptic is the opposite of being dogmatic.

Jamie Hale describes the difference between being cynical and being a skeptic.

“Cynics are distrustful of any advice or information that they do not agree with themselves. Cynics do not accept any claim that challenges their belief system. While skeptics are open-minded and try to eliminate personal biases, cynics hold negative views and are not open to evidence that refutes their beliefs. Cynicism often leads to dogmatism.” 5

He continues by stating that dogmatism “opposes independent thinking and reason.” If we want to be successful critical thinkers we need to become much more skeptical and less cynical.

In his TEDTalk Michael Shermer explains the relationship between the process of skepticism and science.

Skeptics question the validity of a particular claim by calling for evidence to prove or disprove it. In other words, skeptics are from Missouri -- the "Show Me" state. When we skeptics hear a fantastic claim, we say, "That's interesting, show me the evidence for it."6

A key goal here is to encourage you to be more skeptical. Instead of blindly accepting or rejecting claims made by others, take the time to demand proof. Make the person or organization prove the claim they are making. And remember, you need to be open minded when listening to the argument.

Over three centuries ago the French philosopher and skeptic René Descartes, after one of the most thorough skeptical purges in intellectual history, concluded that he knew one thing for certain: “Cogito ergo sum” — “I think therefore I am.”

By a similar analysis, to be human is to think. Therefore, to paraphrase Descartes: Sum Ergo Cogito —I Am Therefore I Think 7

An effective critical thinker who is successful in arguing is a person who is more skeptical of the messages they receive. This advice is not just for those who wish to be argumentative. This advice is for every citizen.

“What we all need, as citizens, is to develop more skill in applying our skepticism. We need to spot false narratives, and also turn aside those who would replace them with pure fiction. Either we get this right or we cease to be free citizens.” 8

The problem we all experience is that it is not natural to be skeptical. Our natural state is to either flee a conflict or stand and argue. This can be explained by how our brains are structured.

Reference

- Deaton, Jeremy. "Cognitive Science Offers Tools To Rebuff Climate Deniers." CleanTechnica, https://cleantechnica.com/2017/03/29/cognitive-science-offers-tools-rebuff-climate-deniers/. Accessed 10 June 10 2017.

- Deaton, Jeremy. "Cognitive Science Offers Tools To Rebuff Climate Deniers." CleanTechnica, https://cleantechnica.com/2017/03/29/cognitive-science-offers-tools-rebuff-climate-deniers/. Accessed 10 June 10 2017.

- Shermer, Michael. "What is Skepticism, Anyway." Awaken, https://awaken.com/2013/02/what-is-skepticism-anyway/. Accessed 30 October 2019.

- Maston, Luke. "Skepticism." The Basics of Philosophy, https://www.philosophybasics.com/branch_skepticism.html. Accessed 10 June 2017.

- Hale, Jamie. "Thinking Like a Skeptic." PsychCentral, psychcentral.com/blog/think-like-a-skeptic/. Accessed 30 October 2019.

- Shermer, Michael. "Why People Believe Weird Things." TED, February 2006, https://www.ted.com/talks/michael_shermer_why_people_believe_weird_things.

- Shermer, Michael. "A Skeptical Manifesto." Skeptic, https://www.skeptic.com/about_us/manifesto/. Accessed 16 November 2020.

- Inskeep, Steve. "A Finder’s Guide to Facts." NPR, https://www.npr.org/2016/12/11/505154631/a-finders-guide-to-facts.

Fight or Flight?

All of your information from your senses goes first to a part of the brain called the Thalamus. We call the thalamus the “flight control center” of the brain. It takes in all of your senses, your hearing, sight, touch and decides how to route the messages it is receiving. One route takes the messages to the cerebral cortex, where our skill in decision-making allows us to contemplate alternatives and make a decision. But if the thalamus is triggered by more intense perceptions, the message goes straight to the Amygdala for action.

We all have an emotional brain that resides in the limbic system, located on top of the brain stem and buried under the cortex. When faced with the stress of an argument, your first reaction is a physical one that begins in an almond sized organ towards the bottom of your brain, called the amygdala. This organ actually keeps a record of your past dangerous experiences and strives to protect you from future harm. As soon as this organ perceives danger, it sends a distress signal to the hypothalamus.

You are taking a nice stroll outdoors when suddenly a snake slithers up on the path in front of you. Emotions are triggered. Oh no, this snake might strike and kill me. Do I stay and defend myself, or flee? You are experiencing, Fight or Flight.

This just doesn’t happen out in the wilderness. It can also happen at work. Your boss is looking for you to assign you a major project. Emotions are triggered, “Oh no I can’t do this,” or “My boss is trying to kill me.” Immediately you think, “I am going to stay and tell him that I can’t do this.” Or “Where can I hide?” This is Fight or Flight.

When the thalamus becomes aware of an emotionally charged perception, the amygdala is sent that perception. Snake! Or Project! Your amygdala has access to your memory and quickly relates the current situation to one of those past memories so it can immediately act. Only later will it look to the logical part of the brain for alternative reactions.

The amygdala swings into action. Immediately:

- Past memories of similar situations are examined

- Adrenaline is pumped into the body which prompts quicker physical reaction

- A surge of energy is experienced

- Stress hormones are activated

- Your pain threshold gets higher

These processes are so intense it may take you 20 minutes before you can get these emotions under control and allow the more logical part of the brain to take over and help with the decisions. This, by the way, explains read rage and why we should wait until the next day to respond to an email that has angered us.

While in this condition, you lose the ability for in depth thinking. The amygdala does not want you to look curiously at the snake and wonder, “What type is it?” No, it recognizes potential danger and is preparing you for survival. If you have ever had a stressful situation and then asked yourself afterwards, “What was I thinking?” The answer is, you weren’t. The brain was preparing you for your “fight or flight” mode and not allowing you to really think. There is no time to think. This is also an explanation for why we often think of something very witty to say to someone, after they have left.

If the situation is so emotionally charged, like a snake or project, then the emotions may totally take over your thoughts and reactions, creating a condition called “emotional hijack.” A way of expressing emotional hijacking is road rage. The impact of the perception is so strong that the emotions take over. Logic does not enter into it. Think about the time your partner did something that finally was the proverbial “last straw” or someone you may be supervising made the same mistake for the tenth time. Did you make an outburst that you now wish had been handled in a different way? All of this happens, before the rational part of our brain, the cerebrum, is asked for guidance.

Now, if we can get the amygdala under a bit of control, our cerebrum is notified of the danger and we now have a chance to think of alternative actions. Instead of just responding with the first reaction that occurs from our memory, we now have the opportunity for more in depth thinking.

A very useful formula to remember is E + R = O.

- “E” stands for Event and refers to some action that has happened to you.

- “R” stands for either Reaction or Response. Reaction is our quick, unthinking answer to an action while a Response is more of a thought our answer where we look at alternatives and select the best one for us in that situation.

- “O” stands for Outcome.

We can't always control the Event that happen to us, but we can create more desirable Outcomes if we Respond to a situation instead of just Reacting to it.

I find it very interesting that your brain gets you ready to either fight a perceived danger or flee from a perceived danger. Even before you are totally aware of the threat, you are in that state of fight or flight. Do you flee or stay and fight? I am hoping that this text will give you the skills to stay and fight in arguments and not flee from them. There are certainly a variety of ways to disagree with someone.

Ways to Disagree

When we arrive at a point where we disagree with the claim being made, we find that there are several ways we can respond. In his essay, How to Disagree, Paul Graham describes a hierarchy of seven ways a person can respond to an argument. Here is his, list starting with the most basic way people react to a disagreement and working up to a more academic method of arguing.

- Name Calling – Totally ignoring an argument and instead just calling the person issuing the argument

an unwelcomed name. You probably did this as a small child to your siblings or playmates.Example:

“You’re just crazy.”

- Ad Hominem – Attacking specific aspects of the source of the argument without referencing any

aspect of the actual argument.Example: “You don’t have a college degree, what do you

know?”

- Responding to Tone – Attacking the tone of the argument, instead of and of the actual content of the

argument. Example: “Wow, your tone is way over the top, don’t you think?”

- Contradiction – Disagreeing by just stating an opposing side, with virtually no actual evidence to

support this presented argument.“No I didn’t” or “You’re wrong, basketball is a better

sport than football.”

- Counterargument – Contradicting the initial argument, but also backing it up with reasoning and evidence.

This is an actual argument and what the author, Graham, considers the first form of

a convincing disagreement.“No, the death penalty does not deter crime. In Ohio when

they initiated the death penalty, crime actually increased.”

- Refutation – Here instead of making a unique counter argument, a mistake in the initial argument

is found, and an explanation of that mistake along with evidence and reasoning is

presented. Here no new argument is made; we are just finding the weakness in the initial

argument.

- Refuting the Central Point – Explicitly refuting the main point of the initial argument. Instead of refuting some of the supporting parts of an argument, here we focus on the key, central point of the initial argument.1

Reference

- Graham, Paul. "How to Disagree." PaulGraham.com, http://www.paulgraham.com/disagree.html. Accessed 30 October 2019.

Two Sides to an Argument

There are two sides to every argument. The two sides are called the pro-side and the con-side. The pro-side will speak in favor of the topic of the argument or what we call the claim being made, while the con-side will be speaking against the claim being made in the argument. There is no third position of an argument like, “I don’t know.” You are either for or against the claim. When you clash against an argument you are taking the con side of the argument.

A discussion is different. In a discussion, you can have a variety of different opinions on a topic. But when you get to the point of deciding on a particular answer, you have an argument. To better understand this, we need to look at the structure of the argument. And to do that we need to go back 2500 years to the Greek foundation for argumentation.

Enthymemes and Syllogisms

We often argue in what the Greeks referred to as an enthymeme. There are two parts to this type of argument, an observation that leads to a conclusion. Examples of an enthymeme could include:

- Ernie is going to be a violent person because he plays violent video games.

- If Terri exercises often she will be healthy.

- Vote for John Doe, he won’t raise taxes.

- Bill Gates is brilliant because he started Microsoft.

This list of arguments contains an implicit assumption. For example: “Ernie is going to be a violent person because he plays violent video games” implies that “people who play violent video games become violent people.” These general assumptions are left out in many, many arguments. The person making the argument assumes that you will just accept the general assumption. The Greeks decided to add this assumption as the third part of their argumentative analysis.

To expand the argument the Greeks used a format called the syllogism. This format is a form of deductive reasoning that starts with two initial propositions that lead to a conclusion. The initial proposition is the assumption implied in the enthymeme.

All professors are brilliant.

Jim Marteney is a professor.

Jim Marteney is brilliant.

First note that the name of any professor could be placed here.

As accurate as we might like the conclusion to be in this argument, what if we found one college professor that was not brilliant? This Greek style of argumentation was an all or nothing approach. The argument was either 100% valid, or 0% valid. Classical Greek argumentation would suggest the entire argument is invalid and we could never make any conclusions.

But, in critical thinking we would argue that if there is just one example of a professor who is not brilliant there is still a high degree of validity, or probability, that the conclusion is still accurate. The argument may still be valid enough to reach the threshold of the target audience to accept the claim. In critical thinking, we make decisions when an argument reaches our threshold. The threshold does not have to be absolute 100%. Even in a court case that threshold is “Beyond a Reasonable Doubt” and not “Beyond any Doubt” which is less than 100% certainty.

This realization was the basis for Dr. Toulmin’s approach to analyzing arguments.

Toulmin Approach to Argument

In order to determine the most effective strategy to respond to a case, the con-side of an argument needs to analyze the argument to discover the strengths and weaknesses of the pro-side. The Toulmin Model gives us an effective tool to successfully clash with the pro-side.

Stephen Toulmin was one of the modern-day leaders of rhetorical theory. He looked at the classical structure of arguments, and found a problem. The conclusions of the classical approaches to arguing needed to be absolute. That is, the conclusions of a correctly structured argument were either absolutely, 100% valid (true) or absolutely 0% invalid (untrue). There were no grey areas.

In his work on logic and argument, The Uses of Argument (Toulmin, 2008), Toulmin defines six parts that make up an argument:

- Claim

- Grounds

- Warrant

- Backing

- Reservations (rebuttals)

- Qualifier

In this approach he breaks down an argument into its component parts to demonstrate the degree of confidence you should have in the argument. Analyzing the argument allows the con-side to determine the strengths and weaknesses of the argument, so a counter argument can be effectively delivered.

- Claim: This is the main point or thesis of the argument. This is what the pro-side is attempting to convince you of or trying to prove. If the claim is not directly stated, just ask, “What is the pro-side trying to prove?” In the sample argument, the conclusion, the claim you are attempting to prove is that "Phil’s friends will lead successful lives."

- Grounds: Here is the starting point of your argument that leads to your Claim. This is what you have observed, read or what you believe to exist. In this sample argument, the grounds are that "Phil has several friends who have graduated from college."

- Warrants: This is the overall logical underpinning of the argument. A general rule that can

apply to more than one Grounds. The Warrant can be a universal law of nature, legal

principle or statute, rule of thumb, mathematical formula, or just a logical idea

that appeals to the person making the argument. Warrants usually begin with words

like; all, every, any, anytime, whenever, or are if-then, either-or, statements. The

Warrant is a general rule that has no exceptions. Those come later

- Warrants are important because they provide the underlying reasons linking the claim and the grounds. You can infer the warrants by asking, "What’s causing the advocate to say the things he/she does?" or "Where’s the advocate coming from?" In our example argument, the warrant is that “All people who graduate from college are successful.” No exceptions.

- Backing: Backing is the specific data, which is used to justify and support the grounds and

warrant. In Toulmin’s original work, he only includes Backing for the Warrant. I am

adding Backing to also look at the quality of the original Grounds of the argument.

Critical thinkers realize that there must be backing for their statements or they

are merely assertions. When clashing with an argument, we need to look at the quality

of evidence that supports the initial grounds.

- In our diagrammed argument, the Backing for the Grounds are the names of the specific friends who graduated from college. The Backing for the warrant comes from an LA Times article that college graduates earn $1,000,000 more in their working lifetime than non-college graduates do. I like to separate the Backing from the Grounds and Backing for the Warrant as they are two different areas that can affect the strength of the argument. Toulmin makes no such distinction.

- Reservations and Rebuttals: They are the “unlesses” to the Warrant. Reservations do not change the wording of

the warrant. Reservations do not change the “universality” of the Warrant. But Reservations

are exceptions to the warrant. These exceptions weaken the validity of the conclusion

because the Grounds may just be one of these exceptions, thus meaning that the Claim

is invalid. In our example, your uncle has a Reservation to the Warrant. He states

that people who get a college degree will succeed, unless they are lazy. The “unless

they are lazy” is the Reservation to the Warrant.

- Note that a Reservation does not refer to a rejection of the Warrant. In this example "Unless they did not graduate" would not be a Reservation because it implies that the Warrant did not happen. Instead a Reservation is a statement that suggests that even though the Warrant took place, the Claim may not occur.

- Qualifiers: Suggest the degree of validity of the argument. If there is no Qualifier, then the

argument is 100% valid. But if a Qualifier exists then the conclusion is less than

absolute. With a qualifier, the argument is about probability and possibility, not

about certainty. You cannot use superlatives like all, every, absolutely or never,

none, and no one. Instead you need to qualify (tone down) your claim with expressions

like; most likely, many, probably, some or rarely, few, possibly, etc.

- In our sample argument, it is argued that Phil’s friends will “most likely” be successful. The “most likely” is the Qualifier.

Counter Argument Strategies

If you are arguing against this claim:

- You might want to add additional Reservations.

- Unless there is an economic downturn

- Unless they have health issues

- You might want to challenge the backing for the Warrant

- You could suggest that earning $1,000.000 over a lifetime would not automatically make you successful.

- You could argue that there was a problem with the analysis conducted by the Rochester Weekly News

No Absolute Certainties

In argumentation, we don’t deal with absolute certainty of a claim. The skeptic and scientist both have the attitude that there are no absolute certainties. In other words, there are doubts on each claim that is argued. One scientist, R. A. Lyttleton, has described this process as the “Bead Model of Truth.” It is important to note here that Lyttlleton does not use the word “Truth” as the absolute “Truth” but instead uses the word “Truth” to represent the validity of a claim.1

To understand his model Dr. Lyttleton imagines a bead on a horizontal wire. The bead can move left or right on that wire. On the far-left side of the wire is the number which corresponds to total disbelief. On the far-right hand side of the wire is the number 1 which is related to a position of total belief or where you would believe the claim with absolute certainty.

Dr. Lyttleton would argue that the bead should never reach the far left or right end. As additional evidence is presented the belief is true the closer the bead moves to the number 1. The more unlikely the belief is to be accepted the closer the bead moves to 0.

According to Toulmin,

“Any claim is presented with certain strengths or weakness, conditions, and/or limitations. We possess a familiar set of colloquial adverbs and adverbial phrases that are customarily used to mark these qualifications. Such adverbs are: presumably, in all probability, so far as the evidence goes, all things being equal, for all that we can tell, very likely, very possibly, maybe, apparently, plausibly, almost certainly, so it seems, etc. All of these phrases can be directly inserted into the claim being advanced, and as a result, would modify the claim indicating what sort of reliance the supporting evidence entitles us to place on the claim.” 2

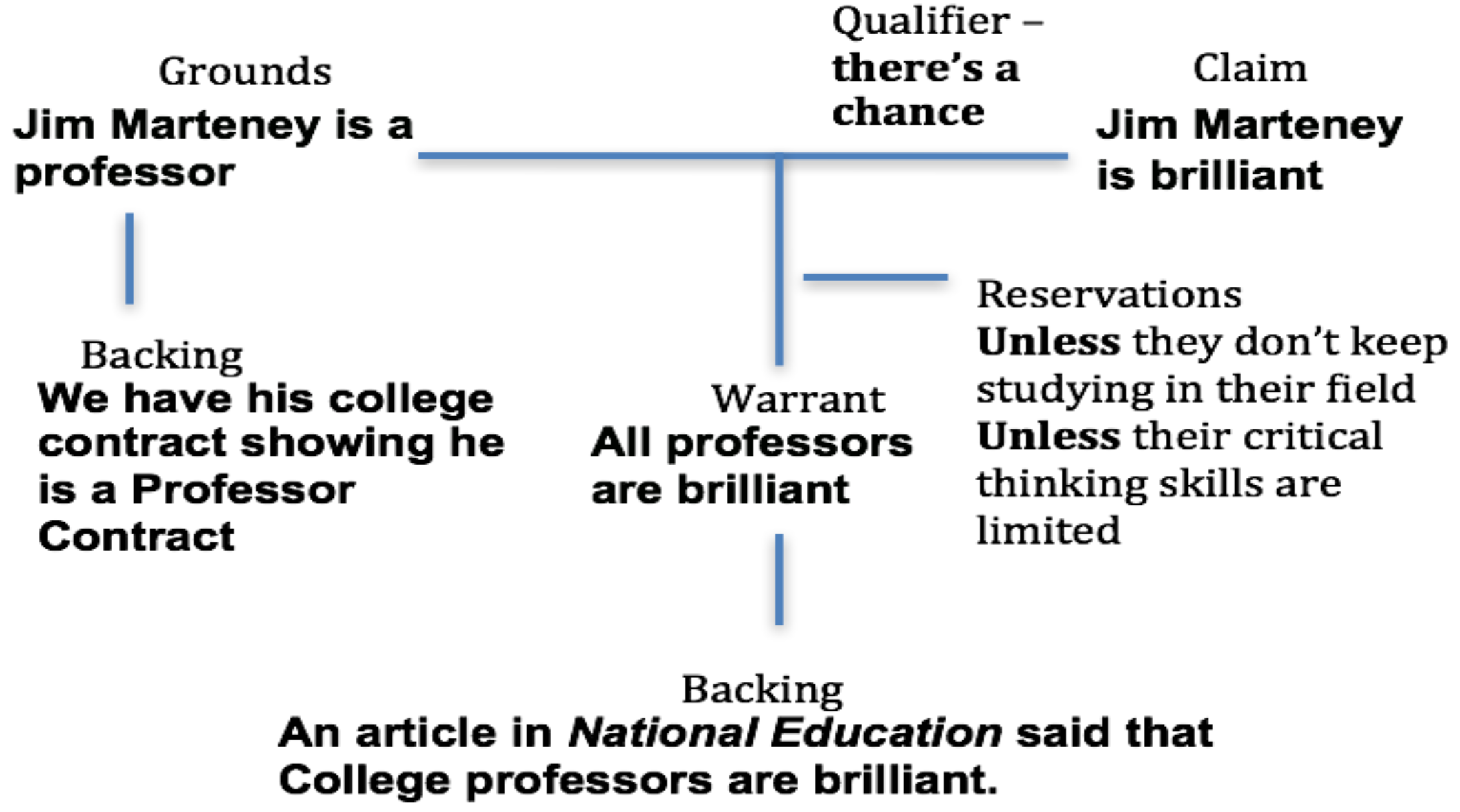

Let’s go back to the “Jim Marteney is brilliant” syllogism. Below is how Dr. Toulmin would analyze the argument. Now you can ask questions about the parts of the argument that are blank, the backing, reservations and qualifier.

The argument as presented is 100% valid because there are no Reservations leading to a Qualifier. There is also no Backing presented for the Grounds and Warrant, so at this point they are just assertions.

- Now you begin your analysis by asking questions, or as we will be calling them, Issues. What is the Backing for the idea that all professors are brilliant? Poor backing would create doubt with the Warrant and its ability to be an absolute, general rule.

- Are there any professors who are not brilliant? If so, that could be part of the Reservation? This is where you show your skepticism.

The answers to these questions could damage the argument. If there are Reservations there is a Qualifier. The more reservations, the weaker the Qualifier becomes the Claim becomes less valid. If there are no exceptions the Qualifier is 100% and you would be 100% certain that the Claim is correct. But with a couple of Reservations your Qualifier could be reduced to maybe 80% sure. Now, does that reach your threshold? There is still a degree of validity, but it may not be enough for you to accept the claim.

Examining the quality of the backing of the Grounds and Warrant might lead us to question the accuracy of those statements. With questionable backing the accuracy of the argument is challenged. The weaker the accuracy the less valid is the Claim.

This is what a completed Toulmin might look like.

With this completed Toulmin analysis of the argument we can immediately see two weaknesses in the argument.

- The publication, National Education which supports the Warrant that “All professors are brilliant,” might be prejudiced in favor of professors. This weakens the accuracy of the warrant.

- Since there are two Reservations to the Warrant, the Claim cannot be 100% valid. There then has to be a Qualifier that suggests a lower level of validity.

Notice that the Qualifier is now, "There's a chance." This would lead me to reject the Claim that Jim Marteney is brilliant.

This is what defense attorneys attempt to do in a courtroom. They don’t have to prove that their client is innocent. They have to attack the prosecution case to reduce the validity of the Claim that their client is guilty. They want the Qualifier to reflect a low number by questioning the backing and adding more and more examples to the Reservations. If in a criminal case they can reduce the validity to below reasonable doubt, the jury should find their client “not guilty.” Notice they don’t say the accused is “innocent.” They can only say that the prosecution did not have a valid enough case for them to find the accused guilty.

Stephen Toulmin developed this model for analyzing the kind of argument you read and hear every day--in newspapers and on television, at work, in classrooms, and in conversation. The Toulmin Model is not meant to judge the success or failure of an attempt to prove an argument; instead it helps break an argument down to its most basic pieces. The Toulmin Model helps to show how tightly constructed arguments are, and how each part of an argument relates to the overall validity or reasonableness of that argument.

Reference

- Hale, Jamie. "Limitations of Science." PsychCentral, https://psychcentral.com/blog/the-limitations-of-science/. Accessed 30 October 2019.

- Toulmin, Stephen E. The Uses of Argument. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2008.

Arguing from the Con-Side

The con-side is the side rejecting the acceptance of the persuasive goal. They are arguing against the Claim by maintaining that we should stay with the status quo, or current system. Assume the Claim being argued is:

- Resolved: The State of California should eliminate capital punishment.

The goal of the con-side is to demonstrate the weaknesses or problems with the change from the status quo to this new policy, and why we should maintain the current capital punishment position. The con-side can win an argument if they just demonstrate there are not enough reasons to change to a new system.

Maintaining the current system is a powerful position. Tradition always suggests that because we have had a certain policy or outlook for so long that there has been some degree of success. So why take the chance and change? Remember, stasis is powerful. We are naturally comfortable with existing ways of doing things and so we argue to continue them. This is one reason why political incumbents have an advantage in an election to be re-elected to office.

Using Toulmin To Develop Con Strategies

After analyzing an argument using the Toulmin approach you can begin arguing against that argument. There are two overall con-side strategies when clashing with the pro- side.

Reducing the significance of the problem or potential advantage. The only reason we ever change from something we have been doing is that there is a significant reason to change. This reason may be that there is a problem that is getting worse and worse, or that there may be an advantage out there if we make the change. Currently more than one state legislature is arguing that all social welfare recipients should be tested for drugs before they are allowed to receive welfare payments. The con-side could argue that the problem is not significant to warrant the change in policy and that the status quo should be maintained.

The Scientific Method

"The real purpose of the scientific method is to make sure nature hasn't misled you into thinking you know something you actually don't know."

--R.Pirsing Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance

This goal then is to weaken the impact of the contentions and thereby the certainty of the Claim is lessened. Those involved grow more skeptical of the Claim. The hope of the con-side is that the certainty of the Claim will fall below the threshold needed to accept the Claim. At this point, the Claim will be rejected and the con-side will win the argument.

The pro-side solution will not solve the problem they intend to solve. The con-side argues that the Claim argued by the pro-side will not work, or in some cases may make the problem even worse. Clashing against the argument that the state should drug test welfare recipients, the con-side may say that the test is not accurate and makes too many mistakes or false positives. They may also talk about how many ways there are to cheat the test. If the con-side can demonstrate that that the pro-side solution cannot work, then the Claim should be rejected.

Creating A Counter Argument

Once we have determined the strengths and weaknesses in the argument by effectively using the Toulmin Model, we can create our counter argument and begin our clash.

In the Toulmin analysis that concluded that Phil’s friend will be successful, two possible counter arguments reveal themselves. One argument can focus on the backing for the Warrant, while another looks at the Reservations.

The Backing for the Warrant “that all who graduate from college will be successful” is from the Rochester Weekly. The con-side might question the quality of that source. How did they determine that conclusion? If the con-side can demonstrate a problem with the Warrant, the entire argument is invalid.

A second con-side argument might be with the reservations. The more significant the reservation that exists, the more of a chance that the instances described in the grounds might apply to those reservations. Maybe Phil’s friends are lazy or picked a poor major. There might be additional reservations like they live in an economically depressed area with few employment chances. The more Reservations to an argument, the less valid is the Claim.

-

Note 1Note 2

-

An argument is not merely denying the claim. Just denying the claim is what we might call “squabbling” or “bickering.” It is not an argument. For clash to be effective you need to explain why the claim should be denied.The con-side does not have to create a counter argument. If they can find problems with the pro-side’s case, they can weaken the validity of the argument to the point where it rests below the Threshold needed to win approval. And thus, the con-side wins the argument.

Con side Case Alternatives

To accomplish the two, overall con-side strategies the con side can select one of the following alternatives.

Straight Refutation

In straight refutation, the con-side directly refutes, point-by-point, the arguments brought up by the pro-side. In using this approach, the con-side argues for keeping the status quo in place. The status quo is the current fact, value or policy that is being challenged by the pro-side. The con-side argues against any of the pro-side case approaches by:

- Refuting the problem and/or solution

- Denying all advantages from a change in the status quo

- Arguing against the alternative(s) being presented

If the pro-side stated that there were two reasons why we need to test welfare recipients for drugs:

- Many recipients of welfare are using drugs.

- Testing will find out who the drug users are.

The con-side using straight refutation would say, “The people promoting the claim state that many recipients or welfare are using drugs, but I argue that there are not that many recipients of welfare that are using drugs.” and “They also say that their tests will find out who the drug users are, but I will argue that the testing that is proposed will not give us an accurate picture of who is actually using drugs. The con-side will still need to use evidence to prove their contentions or else they are just assertions and not real arguments.

Defense of the status quo with just minor repairs

This approach is that the status quo is generally doing an effective job. If there is a problem, it can be dealt with by making a minor change or repair in the status quo. There is no need to make a major change or an overhaul of the system like the claim suggests.

An example of minor repairs occurs when, a couple needs a larger house to accommodate their growing family. Instead of purchasing a new home, they adopt the minor repair approach and add-on to their existing home. Another example is when people avoid the cost of buying a new car by getting their old one repaired.

-

How to Win An Argument Every Time

-

Forbes Magazine, April 23, 2015

https://www.forbes.com/sites/travisbradberry/2015/04/23/how-successful-people-master-conflict/#d79024e788fd

When someone takes an opposing view on a topic you care deeply about, the natural human response is “defense.” Our brains are hard- wired to assess for threats, but when we let feelings of being threatened hijack our behavior, things never end well. In a crucial conversation, getting defensive is a surefire path to failure.

-

How to beat this? Get curious.

A great way to inoculate yourself against defensiveness is to develop a healthy doubt about your own certainty. Then, enter the conversation with intense curiosity about the other person’s world. Give yourself a detective’s task of discovering why a reasonable, rational and decent person would think the way he or she does. As former Secretary of State Dean Rusk said, “The best way to persuade others is with your ears, by listening.” When others feel deeply understood, they become far more open to hearing you.

Counter proposal

In this approach, the con-side admits that the overall goals of the pro-side’s case are good, but the way the pro-side had offered to reach them is not a good approach. In this alternative, the con-side presents what they feel is a better alternative. The con side admits that the pro-side has shown a weakness in the present system, which cannot be denied or refuted. The con side, however, does not agree with the way the pro side wants to remedy the weakness, and offers a better plan of attack.

You and that special someone have been living together for a period of time and are having trouble with the relationship. You suggest that it would be best if you broke off the relationship. The other person agrees that the relationship has problems, but suggests a trial separation would be a better solution. Since both of you agree that the status quo has problems, the argument comes down to which alternative will ultimately gain target audience approval.

Hopefully, after this chapter your confidence is growing and you are more willing to “Clash” with those making arguments with which you disagree.

In the next few chapters we will be looking closely at parts of the Toulmin Model. There is an entire chapter on the Claim, Backing (Evidence), and use of Warrants (Reasoning).

“I don’t mind arguing with myself. It’s when I lose that it bothers me.”

-- Richard Powers

“Anytime four New Yorkers get into a cab together without arguing, a bank robbery has just taken place.”

-- Johnny Carson

The Focus of This Chapter

In this chapter, we examined the skill of “Clashing” when we are faced with an argument that we disagree with. This final chapter looked at the process by focusing on:

- The importance of “Clashing” as “Silence means consent” or at least suggests consent.

- We have different levels of clashing from “name calling” to “refutation.”

- The first step in effective refutation is to examine the argument being presented.

- By using the Toulmin Model we can find weaknesses in arguments that occur in the argument including the backing and/or the inclusion of reservations.

- The more reservations that exist in the argument, the more significant the qualifier, which lowers the validity of the argument on the “Continuum of Certainty.” This could reduce the validity level to below your “Threshold” of acceptance.

- There are three traditional approaches used to refute an argument; Straight Refutation, Defense of the Status Quo with Minor Repairs, and a Counterproposal.

This version of "Clash" based on a previous version that was authored, remixed, and/or curated by Jim Marteney and shared under a Attribution-NonCommercial 2.0 Generic license.